Refugee Rights are Human Rights: The United States is no safe country for refugee survivors of gender-based violence

While settling into work-and-do-everything-else-from-home mode, I’m thinking about those who must leave their homes and brave uncertain and potentially hostile terrain to secure safety and freedom from violence.

Refugees are among those hardest hit by global crises – COVID-19 is no exception. At the time I write this, the border between Canada and the United States is closed to all non-essential travel and all asylum seekers – whether they present at regular border crossings or not — are being turned back. We share the serious reservations being expressed about the illegality, immorality and ineffectiveness of shutting Canada’s doors on migrants.

Canada is a party to the United Nations Refugee Convention, which means it cannot return refugees to countries where they are unsafe and would be in danger. While the Refugee Convention bars Canada from returning refugees to their unsafe country of origin, it doesn’t say anything about sending refugees somewhere else: enter the Canada-United States Safe Third Country Agreement.

We wanted to assist the court in understanding how women and transgender refugee claimants are disproportionately disadvantaged and harmed under this regime.

The Safe Third Country framework allows Canada to designate third countries as “safe” for refugees if those countries are fulfilling their international law obligations under the Refugee Convention and if they have an acceptable human rights record.

The legal challenge was brought by the Canadian Council for Refugees, Amnesty International, the Canadian Council of Churches, an individual litigant and her children. Underway at the Federal Court of Canada, these litigants argue that the Agreement violates the Charter and the human rights of refugees seeking asylum in Canada.

West Coast LEAF applied to intervene in this case. We wanted to assist the court in understanding how women and transgender refugee claimants are disproportionately disadvantaged and harmed under this regime.

Under current United States law, refugees are effectively denied the ability to seek asylum on the basis of a fear of gender-based violence, as many United States immigration judges do not see gender-based violence as grounds for a refugee claim.

On the contrary, while the Canadian refugee determination system is far from perfect, there is explicit, long-standing recognition here of gender-based violence as a basis for protection under domestic and international refugee law. Someone fleeing gender-based violence may qualify for refugee status in Canada, while on the very same facts, they may end up deported from the United States back to the country they fled.

We were disappointed when West Coast LEAF was denied intervener status in the case.

But let’s not forget that uncertainty is nothing new to asylum-seekers who flee their homes to find sanctuary elsewhere. What’s new is that, in these life and death situations, we’ve shut the door and then locked it.

The hearing of the challenge got under way on November 4, 2019. Over four days, the court heard harrowing evidence from survivors and experts in refugee law about just how unsafe the United States is for asylum seekers, especially for those seeking asylum from gender-based violence. The court heard about how refugee survivors of gender-based violence face greater risks of being put in immigration detention, nearly impossible evidentiary thresholds to meet under United States law, and a high risk of being returned to the countries they fled.

The applicants amassed an impressive amount of evidence showing that the United States is not a safe country for refugee survivors of gender-based violence.

The consequence of this reality is that Canada violates the Charter of Rights and Freedoms when it turns refugees back to the United States. It remains to be seen whether the Federal Court of Canada agrees.

Canada’s recent pandemic-related shutdown of its border with the United States is an unprecedented move and one that is contrary to Canada’s legal and ethical responsibilities. The conversation around the border closure has followed a predictable path, that extreme measures are required in uncertain times. But let’s not forget that uncertainty is nothing new to asylum-seekers who flee their homes to find sanctuary elsewhere. What’s new is that, in these life and death situations, we’ve shut the door and then locked it.

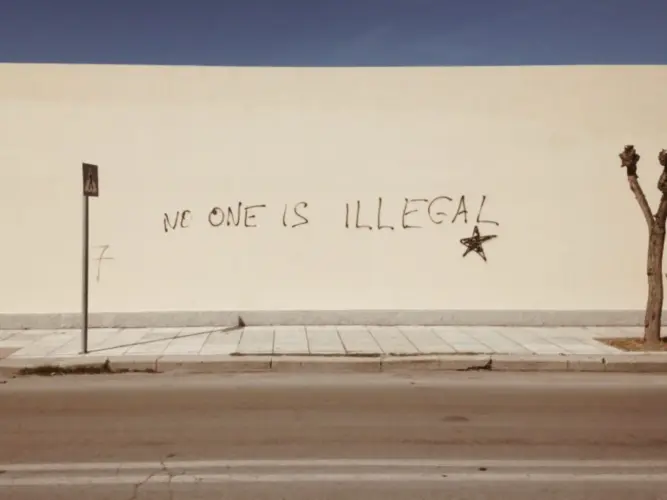

Raji Mangat was raised by immigrant parents on Beaver First Nation and Kelly Lake Metis lands in northern Alberta (Treaty 8). She believes strongly that no one is illegal.

Questions? Comments? Email blog[at]westcoastleaf.org